Everyone is trying to put the massive AI spend by technology companies into context.

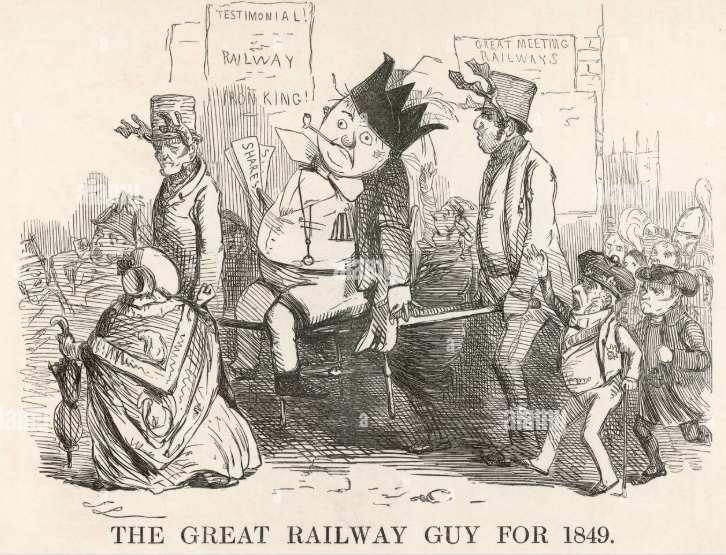

The easiest historical analogies are the telecomm buildout in the 1990s dot-com bubble and the railway bubbles of the 1800s. Each period was defined by excessive infrastructure spending, investor euphoria, and bubbles that popped but still had lasting positive effects.

I’m familiar with the railway bubble because I wrote an entire chapter about that time frame in my book Don’t Fall For It.

While the similarities between then and now are striking, there were far more nefarious activities that occurred during the 19th century.

What follows is a condensed version of what appeared in my book.

*******

Innovation breeds change, change breeds emotion, and emotion adds fuel to the fire when making money decisions.

There’s a reason financial bubbles are called manias — they elicit heightened levels of energy, excitement, and activity. Hucksters are drawn to financial manias like moths to a flame because it’s easier to deceive people when they think humanity is entering a “new era” or “paradigm shift.”

George Hudson saw the British railway bubble of the mid-19th century as an opportune time to profit from the excitement in the air. There was a wave of innovation taking place, and the emotions of the crowd who were looking to get rich quickly led to one of the more underrated historical bubbles on record.

Like most bubbles, the railway mania actually started out as a good idea that was taken too far by investors and those selling railway projects alike.

The first commuter trains appeared in the United Kingdom during the 1820s.

They traveled just 12.5 miles per hour which reduced the trip from London to Glasgow to 24 hours. Without a hint of sarcasm The Railway Times asked, “What more could any reasonable man want?”

The initial railway mania hit in 1825 with the opening of the first steam engine train. An economic downturn snuffed out any speculation and by 1840, shares of the main railway companies were selling at a discount to their issue price (stocks acted more like bonds than stocks back then). At this point, 2,000 miles of track were complete, leading some to speculate that the national railway system in Britain was already finished.

Memories are short when people think there’s money to be made so this first mini-mania in railway stocks became a distant memory by the summer of 1842.

That’s when Prince Albert of the Royal Family persuaded Queen Victoria to make her first train ride. That was the all-clear investors needed to hop aboard the railway-stock train. By 1844, investors viewed these companies as safe and secure, with huge upside potential. It didn’t take long for that cautious optimism to morph into reckless euphoria.

George Hudson was one of the original modern capitalists, using publicity, salesmanship, and a cult of personality to attract enormous amounts of capital and goodwill from the public.

Best described by his contemporaries as energetic, abrasive, bullying, penny pinching, rule-bending and overweight, Hudson was also a shrewd businessman who knew how to persuade people.

Innovation helped trains travel further distances and carry heavier loads so Hudson pounced on the opportunity by creating his own line of railways in the 1830s. Through a series of consolidations, mergers, schemes, bribes, acquisitions, and an uncanny ability to sell, Hudson consolidated more power than anyone in the industry, eventually creating the largest railway company in Britain. By 1844, Hudson oversaw one-third of the total tracks in operation, measuring over one thousand miles in distance.

He was the embodiment of the get-rich-quick era of the railway mania.

Company heads were not paid the astronomical sums CEOs can earn today so Hudson became frustrated with how little he was earning for his work. Cutting corners was his solution to increase his wealth.

Auditing was basically non-existent at the time which allowed Hudson to go nuts.

He did this by keeping his fellow directors and shareholders in the dark about the inner workings of his companies. This included a refusal to hold finance meetings, changes to accounting methods, and general obfuscation about the financial statements. When Hudson joined the board of one railway company in 1842, his first order of business was announcing an immediate change to the company’s accounting methods, proclaiming, “I will have no statistics on my railway!”

Nearly five hundred new railway companies were in existence by the summer of 1845, with stock prices in the sector up a cool 500 percent. As share prices rose during the 1840s so too did Hudson’s bank account.

The palatial estate he purchased at the entrance to Hyde Park was the largest private home in all of London. His name became synonymous with success as the mere mention of his name by promoters provided enough credibility for the sale of stock on a new railway project. Hudson quickly became one of the most prominent figures in the social and political class of Great Britain in the nineteenth century through a combination of wealth, fame, and charisma.

Although he was skilled at selling, Hudson didn’t exactly have to twist anyone’s arm to invest in these new products. Money was flowing in faster than Usain Bolt with the wind at his back.

By June 1945 the Board of Trade was considering over eight thousand miles of new railway, which was four times more than the existing system and almost twenty times the length of England. There were literally plans for tracks that started nowhere and went nowhere with no stops along the way. The estimated cost of the nearly twelve hundred railways under consideration was more than £560 million. That was more than the national income of the entire country!

The most mind-boggling aspect of all this money pouring in is that it all came from private investors.

This wasn’t the government investing in the infrastructure of their country but investors who were looking to get rich.

There were just three railway journals at the outset of the 1840s, led by the Railway Times. By the time the mania reached its zenith in 1845, there were fourteen bi-weekly railway papers, two daily editions, and one which was published every day in both the morning and the evening. At the start of 1845, sixteen new railway proposals were underway and over 50 new companies were formed to meet this demand. Advertisements flooded the newspapers and periodicals. The media pounced on the Queen Victoria train ride, proclaiming the railways as a revolutionary development for mankind, sparking interest from the public in all things rail travel.

Hudson was far ahead of the game in terms of understanding the power of the press and how to use it to expand his empire.

It helped that he had a financial interest in three newspapers that would all run flattering pieces about his projects to attract investors. There is a rumor that Hudson even tried to support a radical new publication called the Daily News and have Charles Dickens as the editor. Dickens was not a fan of Hudson and supposedly remarked, “that he [Dickens] should be the last man in the world to be a supporter of it.”

The schemes worked like this: newspaper ads would promise a 10 percent dividend for anyone who put money into a new railway project. If the project got enough funding, the directors would hold onto a large allocation of shares in the newly formed corporation.

This created enough scarcity to push up the price from the flood of new investors which thereby allowed the directors to flood the market with their shares by selling at a premium price. George Hudson was a master at this scheme, promising unsustainable dividend yields of 50 percent to inflate the share prices on certain issues, which only encouraged more insider trading by himself and the company directors.

These were blatant pump and dump schemes.

The investing public didn’t seem to care. Parliament published a report in the summer of 1845 revealing the identity of twenty thousand investors who had subscribed for at least £2,000 or more worth of railway stocks. Hudson’s name was on there, of course, but so were 157 members of Parliament and almost 260 clergymen.

Investors included the likes of Charles Darwin, John Stuart Mill, and the Bronte sisters. Darwin is said to have lost up to 60 percent in the aftermath of the mania and that was actually much better than most fared in the bloodbath that followed. The rest were mostly regular people, showing how broad the speculation was. Many investors were subscribed for more shares than they could ever hope to pay for but the idea was they would all have the chance to sell at a premium before getting all of their capital called in to create the actual railway projects. Most people assumed the greater fool theory applied but no one planned on being the last fool standing.

The mania was particularly strong in the suburbs because these were the areas that could see the biggest impact from the infrastructure buildout from the new train tracks.

In one town, there was a group of stockbrokers who would take an express train twice a day to relay information from one town to the next on the latest changes in share prices for the railway stocks. Practically all the money for the construction of the railways came from individuals. By 1850, the amount invested was around £250 million, almost half the GDP of Great Britain at the time.

There’s an old saying that markets take the stairs up but the elevator down and the railway stocks were no different. Rising interest rates were the first pinprick in the railway bubble in the summer of 1845. Increased competition and overinvestment finally brought these companies back to earth.

Bankruptcies hit an all-time high in 1846, just a year after the height of the mania. People from all walks of life and levels of wealth were ruined. By the start of 1850, railway share prices had fallen an astronomical 85 percent on average.

By 1849, Hudson’s role as Railway King came to an unceremonious end. Four of the railway companies he was heavily involved in were under investigation.

The shady personal transactions, embezzlement of company funds, overstating of profits, bribing members of Parliament to push his projects through, and insider trading schemes were all made public. The twelve reports produced about his business dealings forever changed public perception of the once-revered businessman. The high society Hudson so eagerly sought to be a part of immediately turned their back on him. Hudson was never prosecuted in a court of law because securities laws at the time didn’t protect shareholders the way they do now.

But he was tried and convicted in the court of public opinion and ostracized by the elite class, which may have been even more of a blow to his gigantic ego.

The press sang Hudson’s praises when things were going well but turned their back on him when things went awry. The Railway Times published what was basically his business obituary but they also came down hard on the investors who went along for the ride:

He no more caused the railway mania than Napoleon caused the French Revolution. He was its child, its ornaments, and its boast. His talent for organisation was prodigious. No labour or speculation seemed to vast for his powers.

He combined and systematised the attacks of a hundred bands upon the public purse; he raised all the fares, he lowered the speed, he reduced the establishments, he ‘cooked’ all the reports, and he trebled all the shares. The shareholders wanted their dividends doubled, and their shares raised to a proportionate market value, They never calculated the extent to which these achievements were honestly practicable, or considered the measures to which it would be necessary to resort. They wanted the trick done all at once and Hudson was the man to do it.

Hudson was able to stay afloat in political life for a few years after the bubble had burst but was eventually arrested for not paying his debts and died broke years later.

A large number of tech start-ups with seemingly good ideas went out of business after the dot-com flameout. But that era planted the seeds for the next wave of innovation that occurred, which gave us services like YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, and Google.

Venture capitalist Marc Andreessen said, “All those ideas are working today. I can’t think of a single idea from that era that isn’t working today.”

The railway boom and bust had some positive outcomes as well. Not all was lost from this period of untamed speculation, greed, and accounting fraud. By 1855, there were over 8,000 miles of railroad track in operation, giving Britain the highest density of railroad tracks in the world, measuring seven times the length of France or Germany.

The railways set up during the bubble years came to represent 90 percent of the total length of the current British railway system. People and businesses across the country experienced massive gains in efficiency through cheaper and faster transportation of raw materials, finished products, and passengers. During the 1840s more than half a million people were employed by the railway companies to make those tracks a reality. Tens of thousands of people from Ireland were provided employment throughout their famine years.

In many ways, this was a wealth transfer from rich and middle-class speculators to the labor class that simultaneously provided the country with much needed transportation infrastructure.

News distribution spread, and the capital markets became more mature. New stock markets were set up in cities all over the country. Stock brokerage firms grew from six in 1830 to almost thirty by 1847. There was greater innovation during the industrial revolution of the eighteenth century but the railway boom required far more capital, and thus investors, so this changed the way the middle class invested their money.

The problem for those trying to handicap the financial ramifications of this innovation is that the economic impact doesn’t always occur at the same time.

Investors extrapolate innovation indefinitely into the future, carrying prices too far, too fast. It took time for the combustion engine to completely replace the horse and carriage. The promises of the Internet came true, but we had to live through the dot-com crash to get there.

Excitement pervades when new technologies are released. Most of the early car companies flamed out.

As car ownership first took off in the 1920s there were 108 automakers in the U.S. By the 1950s, they were whittled down to the big three. The entire airline industry basically lost money or went out of business in the century after air travel was invented.

But investors become so enthusiastic they never stop to wonder what could go wrong, only how the world could change, and more importantly, how rich they will become in the process. The siren song of innovation means there will invariably be a new gold rush every time we collectively get excited about a shiny new toy.

Those innovations may change the way we live but that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re going to make you wealthy in the process.

*******

I wrote this 6 years ago before ChatGPT was a thing and no one was talking about AI. It’s interesting to revisit now.

Is AI the next railway bubble? The next dot-com bubble?

It might not be the worst outcome.

Further Reading:

Type I and Type II Charlatans

Disclaimer: This story is auto-aggregated by a computer program and has not been created or edited by finopulse.

Publisher: Source link