A reader asks:

Is it a good thing or bad thing if someone started investing in that lost decade?

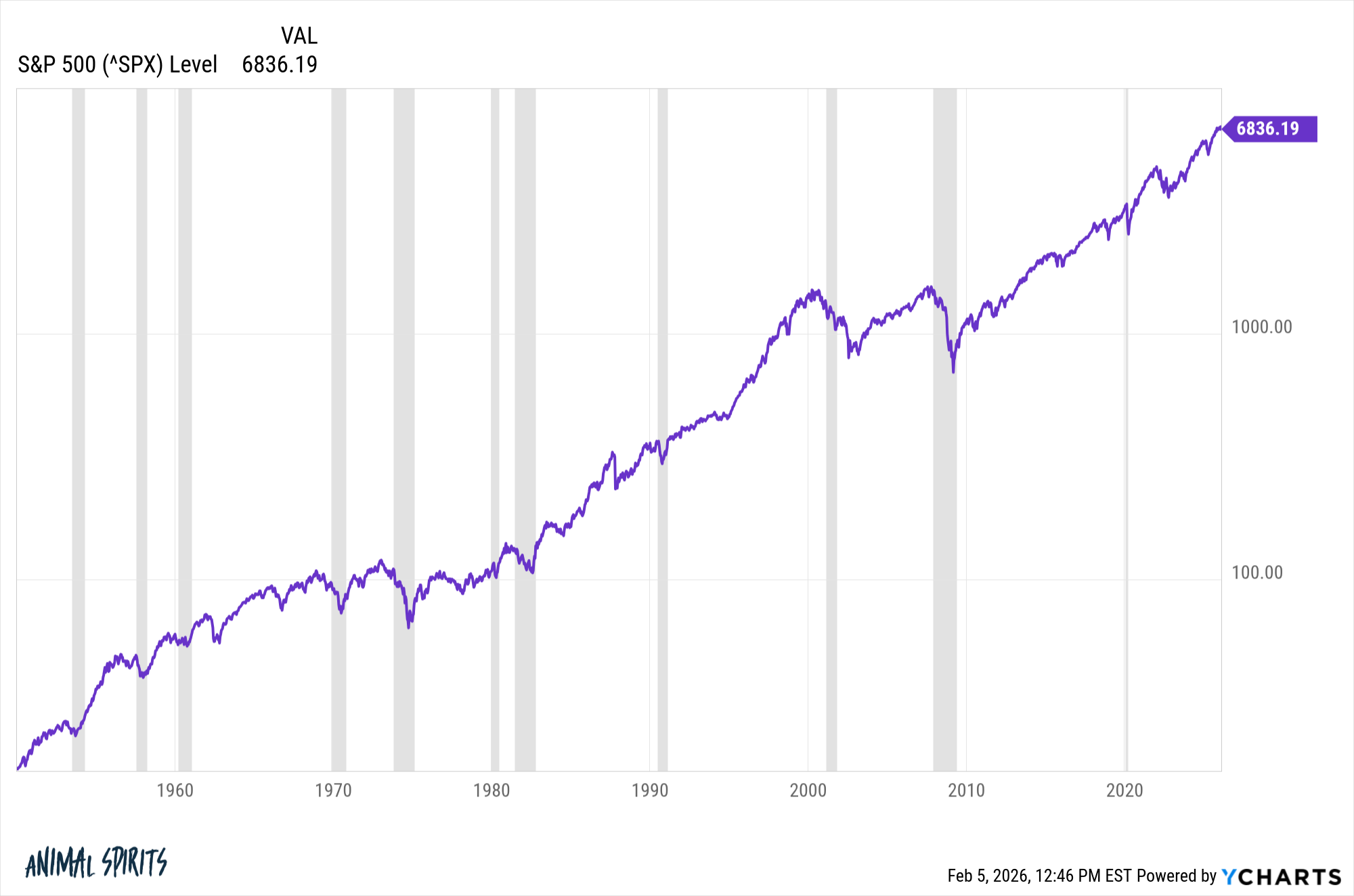

This was a follow-up question to this recent chart I wrote about:

One of these things is not like the others.

It could be a bad thing to start investing during a lost decade if it ruins your perception of risk and scares you away from the stock market. That certainly happened to a decent number of investors following the back-to-back crashes in the first decade of this century.

But for anyone who is a net saver for years to come a lost decade is an ideal way to average into the stock market by consistently buying at lower prices.

Let’s take a look at an example using historical market data to illustrate this point.

Let’s assume you dollar cost average $500/month for 10 years, then let that money ride for 10 years after that.

I did this scenario analysis at the start of 1990 which was a massive bull market and at the start of 2000 which was the beginning of the last lost decade.

In the short run the 1990s situation is much better. The $60k of total contributions would have turned into a little more than $170k. In the 2000s it grew to just $64k (hence the lost decade).

But look at what happens when we extend the time horizon 10 more years:

Dollar cost averaging during a lost decade won by a large margin.

If you’re young, have the stomach for it and dollar-cost-average into the market like most normal people, a lost decade is not something to fear.

They set you up for better returns in the future, which is what tends to happen after a lost decade.

You want the bear markets to come early and the bull markets to come later on.

Speaking of lost decades, another reader asks:

Do you think that free trading websites/apps like Robinhood, Fidelity, Schwab, etc. are helping the market to avoid/disrupt longer bear market periods (2-3 years or sometimes longer depending on economic downfall)? Or do you think that barring some destructive economic crisis that a lost decade is something that could still suffice despite there being continuous inflow from retail?

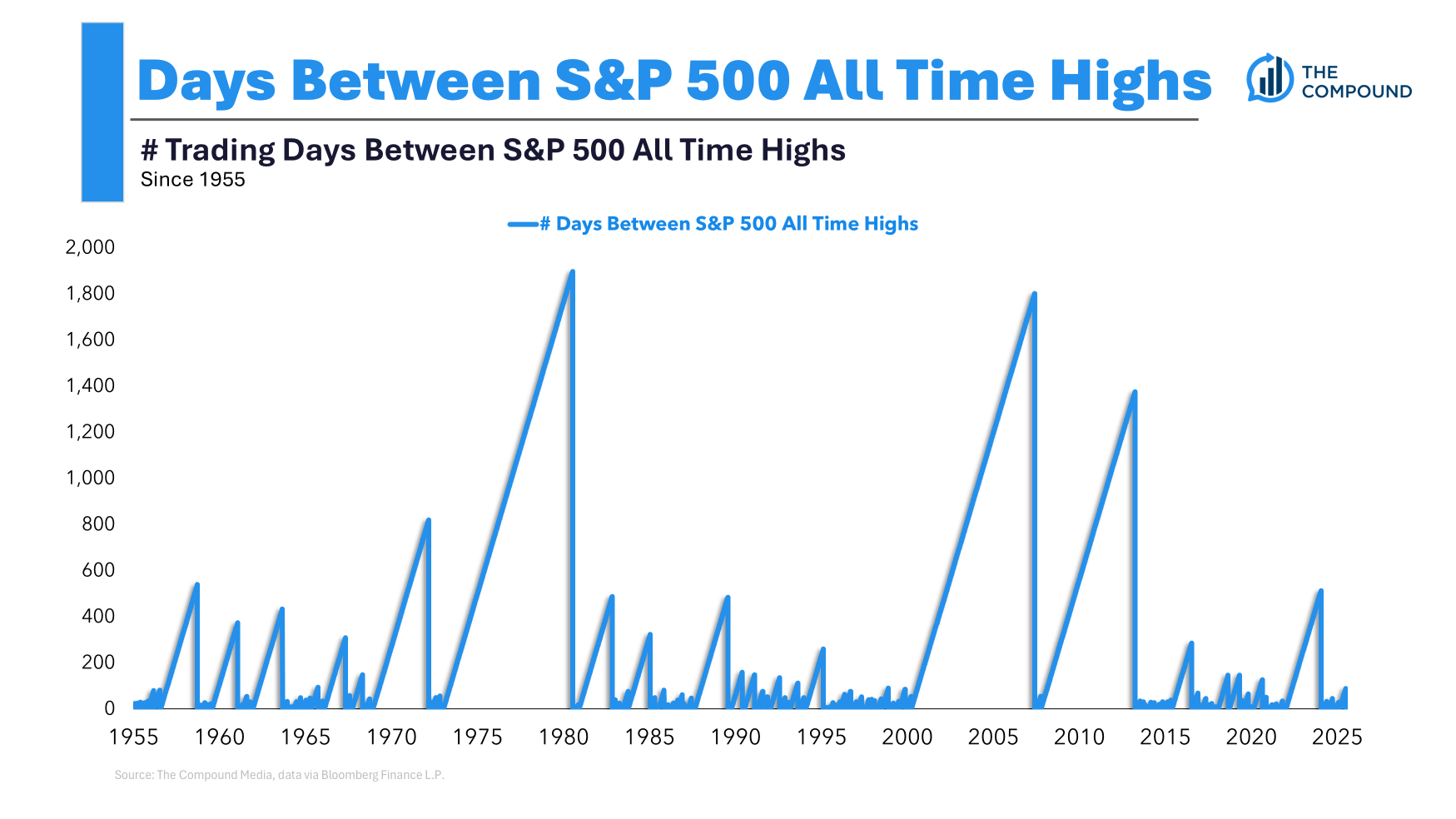

Here’s a chart that shows the number of days between all-time highs on the S&P 500 going back to the 1950s:

To be fair 2022 was a run-of-the-mill bear market where you had more than two years between all-time highs. That wasn’t nearly as bad as some of the other downturns on this chart but it was still an average non-recessionary bear market.

But try to find the 2020 and 2025 bears on this chart. They barely even register because they were over so quickly.

There is something to be said about the nature of recoveries and the fact that investors are conditioned to step in and buy. That was a big reason the April tariff kerfuffle was over so quickly:

Buying the dip is an American pastime.

The information age, social media and algorithms have absolutely sped up market cycles.

However, there are also times throughout history when a gap exists between financial crises.

From the bottom in World War II through the end of the Go-Go Years in the late-1960s there wasn’t a single financial crisis or stock market meltdown.

There were corrections. There were bear markets. There were a handful of mild recessions. But there weren’t any bone-crushing crashes that leave an indelible mark on investor psyches.

Take a look:

Starting with the 1968-1970 crash (which was worse than you think), you had sky-high inflation in the 1970s, an even bigger crash in 1973-74 and a generally dreadful decade for risk assets.

So you had a period of relative calm followed by a period of rough times.

And that period of rough times was followed by a period of relative calm.

After back-to-back recessions and a nasty bear market in the early-1980s (caused by Paul Volcker taking interest rates to like 20%), you had another calm environment from essentially 1983 to the peak of the tech bubble in the spring of 2000:

Sure, you had the 1987 crash but the stock market still finished up that year and it was off to the races immediately following that flash crash. There were some corrections and a recession in 1990 but no financial crises that caused a lost decade or systemwide crash.

That period of calm led to the lost decade. Noticing a pattern here?

You get the lost decades because of deep recessions and/or financial crises. The lost decades — the 1930s, 1970s and 2000s — were littered with banking crises, deep recessions, macroeconomic instability and policy errors.

Retail and automated investing have certainly helped when it comes to the length of corrections but we haven’t had a real recession in over 15 years.1

Market structure is much different today with automated investing, a buy the dip mentality and far more government intervention than we had in the past.

But a financial crisis situation is a whole other ballgame. We need to experience one of those unfortunate events to put this theory to the test.

And it will happen at some point…I just don’t know when.

Periods of relative calm inevitably lead to periods of unrest.

Human nature more or less guarantees it.

We discussed both of these questions in more detail on this week’s Ask the Compound:

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x7DVfjSJtCQ[/embed]

We also answered questions about taking out 84 month auto loans, my views on Bitcoin as an investment and how to automate your health.

My colleague Joey Fishman also joined us on the show to answer a question about late-stage private company stock options.

Further Reading:

Investing a Lump Sum at All-Time Highs

1The Covid blip recession doesn’t count.

Disclaimer: This story is auto-aggregated by a computer program and has not been created or edited by finopulse.

Publisher: Source link